If you have ever spent time around individuals over the age of 65, you may have heard someone complaining of having shingles. The name shingles originates from the Latin word “cingulum,” which means belt or girdle. This is due to the belt like pattern of blisters or vesicles that appear on skin. Some may wonder why these blisters appear in the pattern that they do. With a little research, they will find out that the answer lies within the nervous system.

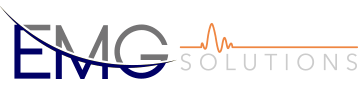

Shingles, medically known as herpes zoster, is connected to the same virus that causes chickenpox- varicella zoster. In fact, it is the reactivation of the varicella zoster virus that has been staying dormant in the nervous system- specifically the dorsal root ganglia (see Figure 1) or the sensory ganglia of the cranial nerves. This reactivation is most commonly seen in individuals aged 65 and older, who are immunosuppressed, and occurs in women more than men, and in white individuals more than black.

This reactivation is believed to occur when the immune system fails to control the latent replication of the virus. Triggers of this reactivation include:

- Emotional Stress

- Figure 1: Use of medications- immunosuppressants

- Acute or chronic illness

- Exposure to the virus

- Presence of a malignant tumor or cancer

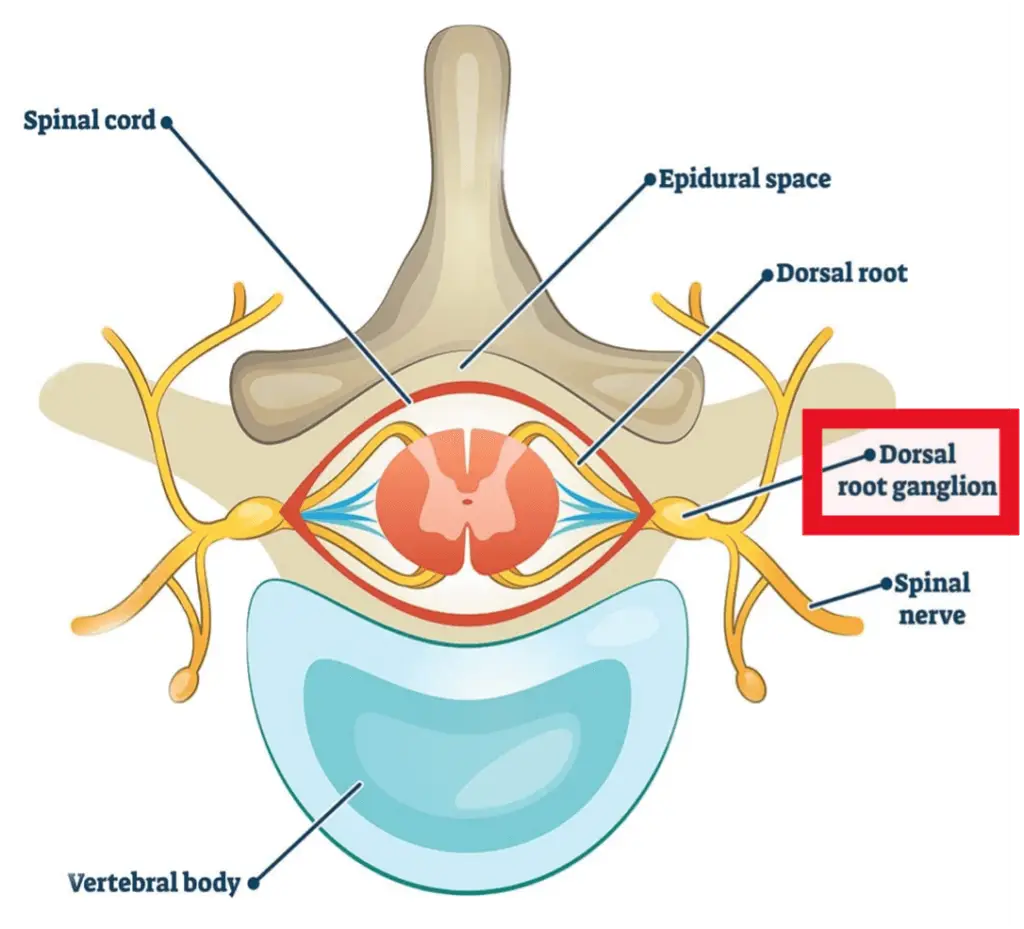

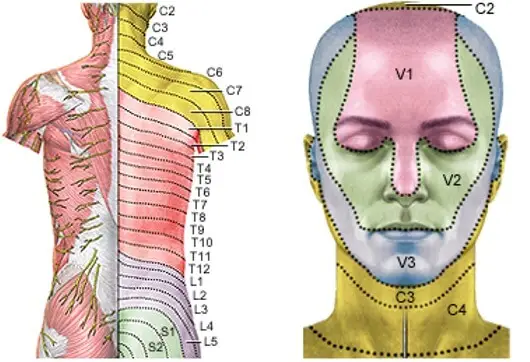

When reactivated, the virus replicates in the nerve cell body, sheds from the cell body, and travels to the area of the skin innervated by the sensory or dorsal root ganglion where the virus has been lying dormant. The area of skin from a dorsal root ganglion is called a dermatome and affects anywhere from the neck to the foot (see Figure 2). When in a cranial sensory nerve (i.e., trigeminal nerve or 5th cranial nerve), it will affect certain areas of the face (see Figure 3). The order of the areas affected from most to least affected is thoracic (mid-back), cervical (neck), trigeminal (face), and lumbosacral (low back).

When the virus is affected, there are generally 3 phases of the infection.

- Pre-eruptive: At least 48 hours prior to dermatomal lesions. Abnormal skin sensations or pain. May also experience headaches, general malaise, and photophobia.

- Acute eruptive phase: vesicles and rash in a dermatomal pattern that are painful and may itch. Vesicles rupture, ulcerate, and crust over. Very painful and may last 2-4 weeks.

- Chronic infection phase: recurrent pain lasting 4+ weeks. May also still experience paresthesia, dysesthesia, and shocking sensations. Continued pain is called post-herpetic neuralgia.

Because the symptoms and phases of shingles are distinct, it is typically diagnosed based on the symptoms. Occasionally, shingles will occur with atypical presentations including no painful rash or vesicles (known as zoster sine herpete). In this case, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test is performed. It requires a swabbing of an open vesicle or through saliva, although it is not as accurate when saliva is tested.

At times, although rare, shingles may be accompanied by other complications. These complications usually involve the nerve or nervous system in locations differing from the locations described above. Some of these complications include the following:

- Segmental Zoster Paresis- muscle weakness seen in the muscles innervated by the dermatome levels that were affected and had rash and vesicle pattern.

- Mononeuropathies- inflammation and damage to a single peripheral nerve (ie. median nerve) causing weakness and decreased sensation.

- Brachial Plexus Neuritis- inflammation and nerve damage in the brachial plexus- a network of nerves between the shoulder and neck to the muscles and skin of the shoulder and arm.

- Myelitis- inflammation of the spinal cord

- Encephalitis- inflammation of the brain

- Ramsay Hunt Syndrome- when it affects nerves in a part of the brain that causes facial pain, hearing loss, vertigo, and/or vesicles (rash) in the ear.

For individuals suffering from the typical form of shingles or who start to notice any of the rare symptoms and conditions, a consultation with a doctor is recommended. They will help guide your treatment. Shingles can be treated with anti-viral medications- like acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir. Some of the rare complications above mimic, or are associated, with other orthopaedic conditions. A doctor may request additional diagnostic testing. This testing may include a referral for a nerve conduction study (NCS) and electromyography (EMG) that will assess for the location and severity of the nerve damage. Another test is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which may see where inflammation is present in the spinal cord, dorsal root ganglion, or somewhere along the length of the nerve as well as other possible musculoskeletal issues. These are tools that will help the doctor understand the condition of the nerves and will help guide the management of a patient’s condition and if there is further intervention needed.

Resources:

- Nair PA, Patel BC. Herpes Zoster. [Updated 2021 Nov 2]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441824/

- Liu, Y., Wu, B. Y., Ma, Z. S., Xu, J. J., Yang, B., Li, H., & Duan, R. S. (2018). A retrospective case series of segmental zoster paresis of limbs: clinical, electrophysiological and imaging characteristics. BMC neurology, 18(1), 121. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-018-1130-4

- Meng, Y., Zhuang, L., Jiang, W., Zheng, B., & Yu, B. (2021). Segmental Zoster Paresis: A Literature Review. Pain physician, 24(3), 253–261.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, February 3). Shingles (herpes zoster). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved September 23, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/shingles/index.html