Many clinicians in various settings perform a physical examination of the patient. The neurologic screen is an important component of the physical exam and typically follows the subjective interview of the patient. While much can be said about conducting an effective patient interview, that will not be discussed in detail here. The end result of the patient interview is summarized as follows: In a time-efficient manner, the patient should feel that they have been listened to and been allowed to tell their story and the clinician should have obtained enough information through listening and effective, clarifying questions that they have a concise list of conditions/pathology used for formulating a differential diagnosis. With this information, the physical exam can be planned and conducted in a way that further rules in or rules out conditions/pathology on the list of differential diagnosis. This physical exam can, of course, vary widely depending on the scope and depth of the body systems being assessed. This post will focus on assessing primarily the nervous system and as indicated in the title of this blog, is written from the perspective of a physical therapist performing nerve conduction and electromyography testing. Therefore, the emphasis of this screen will focus on differentiating neurologic compromise of the peripheral nervous system (radiculopathies, plexopathies, mononeuropathies, and peripheral polyneuropathies) from muscle disease, central nervous system lesions or disorders, motor neuron disease, or musculoskeletal conditions masquerading as one of the former.

The neurologic exam described here is intended to help answer a few specific questions:

- Is there a lesion or dysfunction of the nervous system?

- Is the lesion or dysfunction likely coming from the central or peripheral nervous system (or both)?

- If it appears to be from the peripheral nervous system, can I narrow down the differential diagnosis list?

- Is another diagnostic test or outside referral necessary?

To answer these questions, this neurologic exam will initially be more of a screening rather than a complete neurologic assessment.

This neurologic screen will assess basic function of motor and sensory nerve fibers of the peripheral nervous system and their interconnection to the central nervous system (such as reflexes). It will not be a complete assessment of movement disorders (such as Parkinson’s disease) with tests of coordination, balance, tone/rigidity, etc. Nor will it be a complete ASIA classification exam (for spinal cord injuries).

This screen will assess the strength of the neuromuscular system through active range of motion and resisted strength testing. It will not be a thorough orthopedic examination with precise manual muscle grading or special/provocative tests of musculoskeletal tissues.

This screen will help to further whittle down the differential diagnosis list and answer the questions listed above. It will not lead to a definitive medical diagnosis.

The following sections will detail the components of the neurologic screening while noting clinical interpretation. In practice, this may be performed with emphasis on the upper extremities, lower extremities, or all extremities.

Components of the Neurologic Exam

- Visual Examination and Palpation

- Sensation Testing

- Strength Testing

- Reflex Testing

- Cranial Nerve Testing

Visual Examination and Palpation

Visually assess the patient for signs of muscle atrophy, asymmetries, muscle fasciculations, skin appearance, and facial abnormalities. When assessing the extremities, palpating bony prominences and muscle bulk is helpful to complement what you observe visually.

Admittedly, this section is very long and detailed to read. In practice, this portion of the exam takes about 10-20 seconds for a proficient clinician.

Observe the Face

A few key observations to make are listed below. A more detailed description of cranial nerve testing will be discussed more in detail further down.

- Are there any obvious asymmetries?

- Does one or both eyelids appear tired or droopy?

- Are both pupils the same size?

- Ask the patient to protrude the tongue. Does it deviate to one side? Are there fasciculations/twitching?

Facial asymmetries is obviously a red flag for a cerebrovascular incident.

Droopy eyelids are a hallmark sign of myasthenia gravis, a neuromuscular junction disorder.

Horner’s syndrome is a sign of compromise to the sympathetic (autonomic) pathways to the head and neck, often due to a nerve root avulsion at the C8/T1 levels. Horner’s has a classic triad of signs: ptosis (drooping of upper eyelid), miosis (constriction of the pupil), and anhidrosis (loss of facial sweating).

Tongue movement is innervated by cranial nerve XII, the hypoglossal nerve. Compromise of this nerve (or a compromise of the brainstem) can cause the tongue to deviate to the side of the lesion. Tongue fasciculations are a hallmark sign of motor neuron disease affecting bulbar muscles (innervated by cranial nerves IX, X, XI, XII, originating from the medulla).

Integumentary observations

Examine the skin generally, specifically the extremities under investigation.

- Does the skin look normal? If not, how would you characterize it?

- Are there open wounds? Describe them.

- Is the skin abnormally dry and flaky? Hairless?

- Also look at nails, especially toe nails

Many of these observations provide clues about the presence of a peripheral polyneuropathic processes. As the name implies, this affects many, or all, nerves in the body including autonomic nerve fibers. Therefore, functions such as sweating and general homeostasis of the skin will be impaired. Diabetic neuropathy is among the most common peripheral polyneuropathic processes and will often present with distal hair loss and abnormally thick toenails.

Another relevant skin abnormality that may be noted is the presence of a rash, vesicles, or hair loss in specific dermatome(s) distributions. This may be indicative of a herpes zoster viral infection affecting nerves at the sensory ganglia of cranial nerves or the dorsal root ganglion near the spinal nerve roots.

Palpation of the Upper Extremities

Start by placing hands on the upper traps and assessing the muscle bulk between your thumb and fingers. Work your way down the extremities as listed below, looking for signs of asymmetric bony prominences, atrophy or fasciculations (twitching). You may also discover places that are tender to palpation, reproduce familiar pain, or produce referred pain in a familiar distribution.

When pain or tenderness to palpation is affirmed by the patient, clarifying questions are important:

Is that “your pain” (or, the pain you described to me a minute ago) or something different/new?

Is that painful only where I’m pressing or does it travel anywhere else? If so, where?

Begin palpating proximal to distal (nerve innervations will be listed in orange)

Upper traps

Innervation: Spinal accessory nerve

Slide down to the scapula, feeling the scapular spine and the muscle belly of infraspinatus below the scapular spine, supraspinatus above the scapular spine (beneath the more superficial upper traps).

Innervation: Suprascapular nerve; C5-C6

Slide laterally to the top of the shoulder (AC joint). Continue moving distally to the muscle belly of the deltoids

Innervation: Axillary nerve; C5-C6

Upper arm, biceps and triceps

Innervation: Biceps – Musculocutaneous nerve; C5-C6. Triceps – Radial nerve; C6-C8, primarily C7

Palpate the elbow joint, olecranon, medial and lateral epicondyle

You may test for reproduction of pain at the common flexor origin at the medial elbow and common extensor origin at the lateral elbow. This may clue you into medial or lateral epicondylitis masquerading as a radiculopathy or peripheral compressive neuropathy.

Muscle bulk of the forearm about ⅓ of the way between elbow and wrist

Innervation of anterior medial aspect for flexor muscles: Mostly median nerve (except for flexor digitorum profundus to digits 4-5 and flexor carpi ulnaris, which are both ulnar innervated); C6-C8

Innervation of posterior aspect for extensor muscles: Radial nerve (posterior interosseous branch); C7-C8

Hands

The hands are very important to examine closely for signs of muscle atrophy. Many peripheral nervous system pathologies will present with abnormalities in the hand(s).

- Many peripheral polyneuropathies are length dependent, so muscle loss due to axon disruption will happen distally in the hands/feet first.

- Median or ulnar compressive neuropathies, if severe, can also result in atrophy in the hand.

- Atrophy of hand intrinsic muscles is also among the early signs of motor neuron disease, such as spinal muscular atrophy or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Visualize and palpate the hypothenar muscle bulk (on the medial side of the hand, proximal to the little finger) and first dorsal interosseous muscle (webspace between the thumb and pointer finger). Does it look or feel “sunken in” or different side to side?

Innervation: Ulnar nerve; C8-T1

Next, do the same with the thenar muscle bulk, abductor pollicis brevis (APB) being the most superficial (on the palm between the thumb and wrist). You can place the hands side by side, palms facing each other, to easily compare the muscle bulk of the APB side to side.

Innervation: Median and ulnar nerves; C8-T1

Ask the patient, “grasp my hand firmly” (as in shaking their hand). Then instruct them to let go. If they struggle to release their grasp, this may clue you into something like myotonia, a muscle disease that presents with impaired ability to relax a contracted muscle.

The objective is not to test their grip strength, though you may observe especially weakened grip. Grip strength can be objectively assessed with a handheld dynamometer without risking your hand taking a beating from someone ambitious to demonstrate how strong they are.

Palpation of the Lower Extremities

Beginning with the patient in a standing position is ideal, as it allows observation and palpation of the pelvis and posterior musculature of the hips and thighs.

- With the patient in standing, observe general standing posture. Is there even weight distribution on each leg? What is the position of the trunk and spine (excessive lordosis, kyphosis, side-bent or scoliotic posture)?

- Begin with hands atop the iliac crests. Are they level with each other?

- Slide down to the greater trochanters of the hips.

- Instruct the patient to bend forward as much as comfortable. Observe for rib hump (scoliosis) and feel the spinous process down the length of the spine to appreciate general alignment.

- Cautionary Tip: Do not get bogged down in over-analyzing posture, alignment, pelvic tilt/shift, symmetry of leg length etc. We’re looking for gross abnormalities and patterns here.

Seated position. The clinician may choose to begin the exam with the patient seated for brevity.

Palpate the distal quads

Innervation: Femoral nerve; L2-L4

Slide down to the knee joint, one at time, using both hands on the knee joint to feel the joint line. Is there a palpable mass at the posterior knee (suspicion for Baker’s cyst)?

Continue distally down the leg, feeling the muscle belly of the foot/toe dorsiflexors lateral to the tibial crest and laterally to ankle evertors on the lateral aspect of lower leg

Innervation: Deep fibular and superficial fibular; L4-S1

Muscle belly of the triceps surae (two heads of medial gastrocnemius and soleus)

Innervation: Tibial nerve; L5-S1

Ankle joint – medial and lateral malleolus. Describe swelling/edema

Feet

Palpate the muscle belly of the extensor digitorum brevis (EDB) on the dorsal-lateral aspect of the foot. Instructing the patient to lift their toes up will help to locate this muscle.

The presence of a palpable, well-developed EDB is generally a good sign of healthy nerves. Because it is very distal, it will be affected by a length-dependent peripheral polyneuropathy. You will notice atrophy of this muscle when the lateral dorsum of the foot is flat and bony without any palpable muscle or “squish”.

Innervation: Fibular nerve; L5-S1

If you note a pattern of high arches, clubfoot, and atrophy of peroneal muscles then this may indicate the presence of an inherited polyneuropathy, the most common being Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease.

As noted above, palpation and visualization need only take a minute or less. This will give you preliminary information to keep in mind as you proceed with the rest of the exam. Make note of your observations of skin appearance, muscle atrophy or fasciculations, gross bony abnormalities, general body composition, and presence of edema or swelling. You may also note deformities or scars from congenital conditions or prior injuries or surgeries. All of this will help you appreciate and begin to delineate what is relevant to acute signs and symptoms, what is likely attributable to old or chronic pathology, and what may be irrelevant.

Sensation Testing

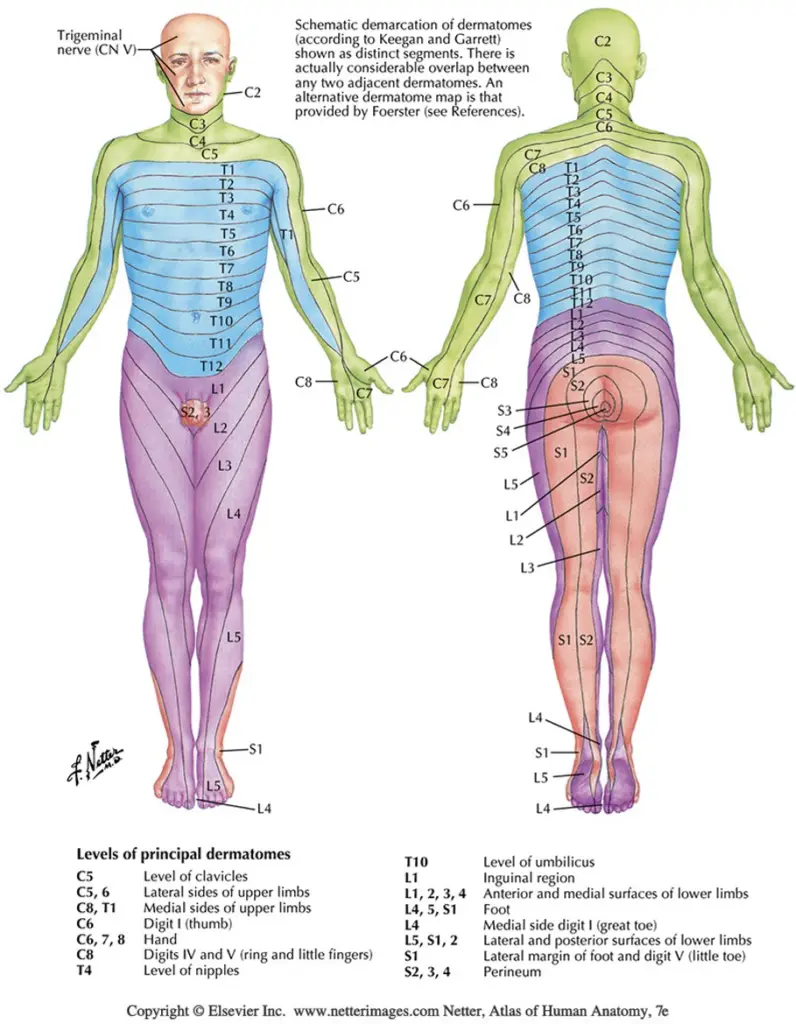

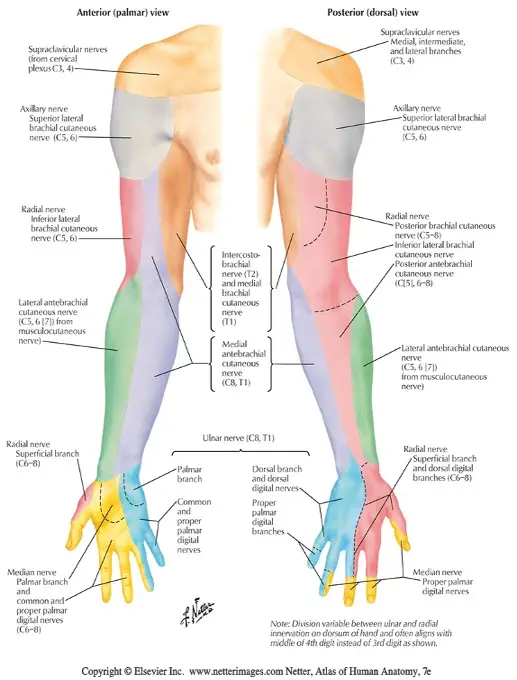

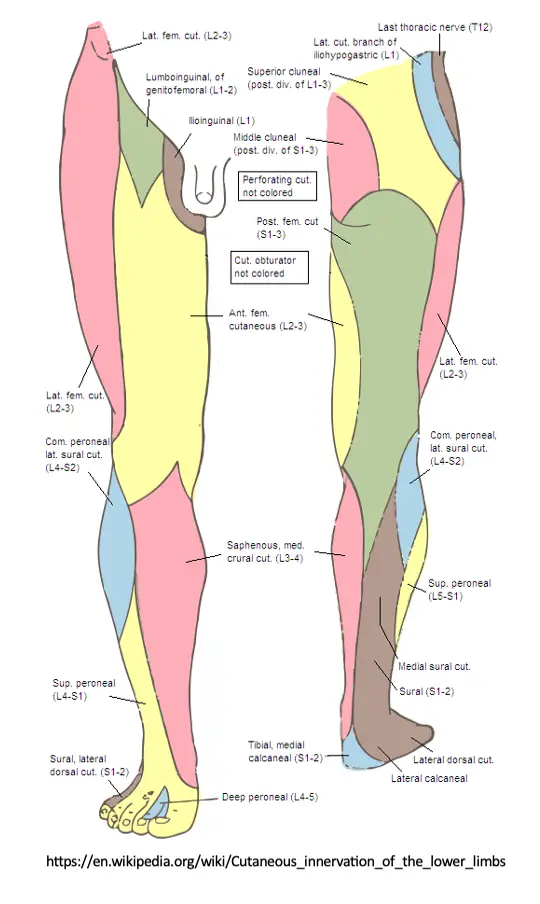

Sensation to light touch, sharp/dull touch, vibratory sense, and other methods assess the afferent, sensory nerve fibers conducting distal to proximal that synapse in the dorsal root ganglion and continue through the spinal nerve root to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Skin sensation can be assessed with both dermatome and peripheral nerve distributions in mind. Dermatomes refer to the corresponding nerve root level that generally supplies/receives sensory information from that area of the body. Peripheral nerve distributions refer to single nerve territories, distal to their branching from the plexus and spinal nerve roots. See diagrams below.

Light touch sensation testing is the least reliable, yet easiest to perform. Differentiation between sharp and dull touch is more reliable and informative. Assessing sensation with a tuning fork has been shown to be very effective and statistically sensitive for loss of protective sensation, as vibration sense can be one of the first sensations to be impaired by a neuropathy.

It is important to remember that nerve distributions can vary from person to person and there is considerable overlap between dermatomes. Careful testing and looking for patterns of findings will help to arrive at the correct conclusions. Listed below are common body regions for dermatome testing.

C1: Top of the head

C2: Posterior occipital region

C3: Side of the neck

C4: Top of the shoulder

C5: lateral deltoid

C6: Tip of the thumb

C7: Distal middle finger

C8: Distal fifth finger

T1: Medial forearm

L1: Inguinal region

L2: Anterior mid-thigh

L3: Distal Anterior thigh

L4: Medial lower leg/foot

L5: Lateral leg/foot

S1: Lateral side of foot

S2: Plantar surface of foot

S3: Groin

S4: Perineum region, genitals

Most neurologic screens will assess dermatomes C4-T1 and L2-S2. Other dermatomes can be assessed if indicated by the subjective exam.

Technique

This is generally conducted in a proximal to distal manner down the upper and/or lower extremities, similar to the approach taken for the visual examination and palpation performed previously.

To assess light touch sensation, using a cotton swab or small brush is optimal, though many clinicians simply use their hand/fingers to lightly stroke the area being tested. Ask the patient, “Does this feel the same or different side to side?” When the patient notes that there is a difference you may question further to clarify if it feels more dull, tingly, hyper sensitive, etc. However, simply noting that it is altered or diminished compared to the contralateral side or other nerve distributions is usually sufficient.

Assessing sharp/dull sensation is performed with a pin that has a sharp point on one side and a blunt end on the other side. Instruct the patient to close their eyes and tell you if they feel it on their left or right side and if it is sharp or dull. Conduct this in a random manner so as to prevent the patient anticipating the location and type of stimulus.

Listed next is an example of a routine that covers the vast majority of the relevant dermatomes and peripheral nerve distributions. The primary focus is on dermatomes, however keep in mind peripheral nerve distributions. Assess these areas with light touch and sharp/dull.

Upper Extremities

Seated with hands resting on lap, hands pronated

Body Region: Lateral shoulders

Innervation: C5/C6. Axillary

Body Region: Dorsal webspace/Thumb

Innervation: C6. Radial (superficial radial)

Body Region: Posterior forearms

Innervation: C7. Posterior cutaneous nerve of forearm

Body Region: Second/Third Finger

Innervation: C7. Median

Body Region: Fifth Finger.

Innervation: C8. Ulnar

Median vs Ulnar peripheral nerve comparison. Because median and ulnar neuropathies are very common (ie. carpal tunnel syndrome and cubital tunnel syndrome), it is beneficial to appreciate median compared to ulnar sensation differences.

Medial (lateral) compared to Ulnar (medial) side of the fourth digit. “Does this side of your finger feel different than this side?” as you provide light touch alternately to either side. The same can be done between the fifth digit and second digit.

Hands pronated

Body Region: Medial forearms

Innervation: T1. medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm (medial antebrachial cutaneous)

Body Region: Lateral forearms

Innervation: C5/C6. lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm (lateral antebrachial cutaneous)

Lower Extremities

Patient in a seated position

Body Region: Anterior mid thigh

Innervation: L2. Anterior femoral cutaneous

Body Region: Distal anterior thigh

Innervation: L3. Anterior femoral cutaneous

Body Region: Anterolateral mid thigh

Innervation: L3/L4. Lateral femoral cutaneous

Body Region: Medial lower leg and foot

Innervation: L4. Saphenous nerve (branch of femoral nerve)

Body Region: Lateral lower leg and dorsum of foot

Innervation: L5. Superficial fibular nerve

Body Region: Lateral heel and foot

Innervation: S1. Sural nerve (branch of tibial)

Body Region: Plantar surface of foot

Innervation: S2. Medial/lateral plantar nerve (branches of tibial)

Vibration testing

The literature describes numerous methods for assessing vibration sense which is most often used for detecting loss of protective sensation in the diabetic foot. The method described here (“On/Off”) is chosen for its simplicity and time efficiency.

Using a 128Hz tuning fork, assess the patient’s ability to determine if/when the tuning fork is vibrating and when it stops.

1- Strike the tuning fork against the palm of your hand so that it vibrates for approximately 40 seconds

2- Apply the base of the tuning fork to the patient’s forehead or sternum to ensure the vibration sensation is understood

3- Instruct the patient to close their eyes and apply the base of the tuning fork to the dorsum of the great toe just proximal to the nail bed. Ask the patient if they feel the vibration.

4- Instruct the patient to tell you when the vibration has stopped. Mute the vibrating tuning fork with your other hand.

5- Repeat this 2-3 times on each foot. Again, randomize if the tuning fork is vibrating or not when initially applied to the toe and the duration of time until you stop the vibration.

6- Normal vibratory sensation will be determined by correct responses at the great toe. However, when vibratory sense is impaired at the great toe, move to more proximal bony prominences to note at which point vibration is correctly identified. (Dorsum of the foot, lateral malleolus, patella, ASIS, pointer finger.)

Strength Testing

Manually testing muscle strength assesses the efferent, motor nerve fibers which originate in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and continue peripherally as spinal nerve roots and peripheral nerves to skeletal muscle fibers. Like sensation testing, strength can be assessed with spinal nerve root origins or more specific peripheral nerve innervations in mind.

Range of Motion Screening

As noted previously, this screen is not intended to be a comprehensive musculoskeletal assessment. However, a simple screen of range of motion can help determine if a movement restriction is likely due to a neurologic compromise rather than an impairment of joint or soft tissue function. For example, a patient with limited active and passive shoulder abduction but who demonstrates good strength in their available range of motion is more likely to have a musculoskeletal impairment of the shoulder girdle rather than a neurologic compromise.

Upper Extremity Range of Motion

Instruct the patient to perform the following movements:

- Reach above your head

- Fully bend and straighten your elbows

- Move your wrists in circles in like this (demonstrate wrist circumduction)

- Open your hand all the way then make a tight fist

- Look all the way up. Now all the way down. Look over your right shoulder, then your left. (Cervical extension, flexion, right/left rotation.)

Lower Extremity Range of Motion

Instruct the patient to perform the following movements:

- March your legs up and down

- Bend your knees all the way back then straighten them all the way

- Pump your ankles up and down all the way then pivot them side to side

Manual Muscle Testing

Testing of muscle strength can be graded on a scale from 1-5, with five being full strength and one being trace/twitch activation. More precise grading with +/- between whole numbers 1-5 is generally reserved for more specific assessment of the musculoskeletal system (though the reliability and validity of manual muscle grading has been challenged). The main purpose here is to identify possible neurologic compromise by determining if strength is normal and symmetric or not.

Again, proceed proximally to distally down the upper and/or lower extremities. Provide simple instructions and demonstrate the position for each movement. Instruct the patient “don’t let me move you,” or “hold strong in this position” for each movement listed below. Also note that each movement is facilitated by multiple, overlapping muscles and nerve innervations. The ones detailed here are the most common innervations, with predominant innervations bolded.

Upper Extremities

Action: Shoulder Elevation

Procedure: “Shrug your shoulders up.” Apply inferiorly directed force to the shoulders

Innervation: C4. Spinal accessory nerve (upper trapezius).

Action: Shoulder Abduction

Procedure: “Bring your elbows out to the side.” Apply force to the elbows towards shoulder adduction.

Innervation: C5/C6. Axillary nerve (deltoids), Suprascapular nerve (supraspinatus).

Action: Elbow Flexion

Procedure: “Arms in front of you with elbows bent.” Apply force at the wrist, pulling towards elbow extension.

Innervation: C5/C6. Musculocutaneous (biceps/brachialis).

Action: Elbow Extension

Procedure: “Push down on my hands” (continued from 90 deg flexed elbow position). Resist the patient’s force into the elbow extension.

Innervation: C6/C7/C8. Radial nerve (triceps).

Action: Wrist Extension

Procedure: “Straighten your elbows and curl your hands back” (with forearms pronated). Apply force to the top of the hands towards wrist flexion.

Innervation: C7/C8. Posterior interosseous nerve, branch of radial (Multiple muscles in the posterior forearm, such as extensor carpi radialis longus/brevis and extensor carpi ulnaris).

Action: Thumb abduction

Procedure: “Hold your hands like this” (demonstrate ‘crab’ hands). Apply resistance to the thumb towards the base of the pointer finger.

Innervation: C8/T1. Median nerve (abductor pollicis brevis).

Action: Finger Abduction

Procedure: “Spread your fingers out wide.” Apply force to the pointer and little fingers towards finger adduction.

Innervation: C8/T1. Ulnar nerve (primarily first dorsal interosseous and abductor digiti minimi).

Action: Thumb IP flexion and pointer finger DIP flexion (OK sign test)

Procedure: “Make an OK sign with your hand. Don’t let me break the ‘O’.” Apply force outward against the contact made by the tips of the pointer finger and thumb.

Innervation: C7/C8/T1. Anterior interosseous nerve (flexor pollicis longus, flexor digitorum profundus to digits 1-2).

Lower Extremities

Action: Hip Flexion

Procedure: “Lift your knee up to my hand.” Apply downward force at the knee towards hip extension.

Innervation: L2-L3. Femoral nerve (iliopsoas, rectus femoris, other hip flexors)

Action: Knee Extension

Procedure: “Kick your legs out straight.” Apply downward force at the ankles into knee flexion.

Innervation: L2/L3/L4

Action: Ankle Dorsiflexion

Procedure: “Pull your feet back towards you.” Apply downward force on the dorsum of the feet towards plantar flexion.

Innervation: L4/L5. Deep fibular (anterior tibialis, extensor digitorum longus).

Action: Great Toe Extension

Procedure: “Hold your big toes up.” Apply downward force on the great toes towards toe flexion.

Innervation: L5. Deep fibular (extensor hallucis longus and brevis).

Action: Ankle Eversion

Procedure: “Point your feet outward.” Apply inward force on the forefoot towards inversion.

Innervation: L5/S1. Superficial fibular (fibularis longus and brevis).

Plantar Flexion: Standing Heel Raises

Procedure: Instruct the patient to perform single leg heel raises with a two-finger balance assist. Normal strength (5/5) is 25 repetitions. Many patients will not be able to perform 25 repetitions and this may not indicate a neurologic compromise. Therefore, contralateral comparison will be useful.

Innervation: S1/S2. Tibial nerve (gastrocnemius and soleus)

Muscle Tone

As you perform range-of-motion and strength testing, you may notice abnormal resistance to movement or tone. Spasticity and rigidity are types of muscle tone. Spasticity is a “catch” in the movement which is velocity dependent, or brought on by fast movements. Rigidity is stiffness that is present in the whole range of motion, generally observed in either flexor or extensor muscle groups. The presence of spasticity or rigidity indicate central nervous system lesions in the pyramidal tracts or extrapyramidal tracts and basal ganglia, respectively.

If spasticity or rigidity is noted during your exam, you may investigate further by performing passive circular and full flexion/extension of extremity joints, adding in random high velocity movements. Rigidity will feel like manipulating a lead pipe, while spasticity will “catch” during the high velocity movements.

Conversely, hypotonia is characterized by floppy or flaccid muscles. This can indicate the presence of other central nervous system pathology or a myopathy (muscle disease).

Clinical Patterns

Upon completion of the components of this strength and movement testing, consider the pattern of your findings. Is there weakness in multiple muscles of the same peripheral nerve? Or is the “common denominator” of the weakness at specific nerve root levels (myotomes).

Also note that generalized weakness in proximal muscle groups (at the hip and shoulder girdle) can be an indication of a myopathy or an autoimmune polyneuropathy such as Guillain Barre Syndrome. However distal, symmetrical weakness may indicate a length-dependent polyneuropathy or even early motor neuron disease.

Reflex Testing

Many types of reflex testing can be performed to assess the integrity of peripheral and central nerve fibers.

Muscle stretch reflexes (or deep tendon reflexes) stimulate muscle spindle receptors in muscle tendons, sending an afferent signal through sensory nerve fibers to a specific level of the spinal cord which synapses directly with motor nerve fibers, resulting in an efferent signal back to the muscle causing muscle contraction. This response is elicited by striking the tendon with a reflex hammer. There are five muscles commonly tested in this manner: biceps, brachioradialis, triceps, quadriceps, and ankle/achilles.

A few additional reflexes are important in the neurologic exam to assess for upper motor neuron lesions. These include the Babinski reflex, Hoffman’s sign, and Clonus reflex.

Muscle Stretch Reflexes

MSRs can be graded using the following scale:

(0) – Absent

(1+) – Trace or hypo-reflexive

(2+) – Normal

(3+) – Brisk or hyper-reflexive

(4+) – Non-sustained clonus

Absent or hypo-reflexive muscle stretch reflexes indicate a lesion of the peripheral nerve, either along sensory nerve fibers towards the spinal cord or motor nerve fibers on the way back from the spinal cord to the muscle. The lesion could be anywhere along the course of the reflex arc: peripheral nerve branch, trunks/divisions/cords of a plexus, spinal nerve root, or neuron pool at the spinal cord.

Hyper-reflexive muscle stretch reflexes indicate a lesion of the upper motor neurons in the central nervous system (brain or spinal cord). Under normal physiologic circumstances, the brain sends inhibitory signals down the corticospinal tracts. A lesion of these descending inhibitory signals results in a muscle stretch reflex that is prolonged or exaggerated.

Some pathologies, such as motor neuron disease, may affect peripheral motor neurons in the anterior horn of the spinal cord AND central motor neurons in the brain or brain stem. In this case, you may observe a combination of hypo-reflexia and hyper-reflexia.

It is important to note that reflexes graded as 1+, 2+, or 3+ could all be normal responses for that person. Some people will have very brisk, reactive reflexes while others’ reflexes are less reactive or more difficult to elicit. Therefore, side to side differences are more significant than generalized bilateral hypo or hyper reflexia.

Consider your reflex testing findings as another piece of the “neurologic system puzzle” you are creating in combination with your subjective report, observation, sensation testing, and strength testing pieces. What picture is being created? A unilateral diminished response of the brachioradialis and biceps reflex raises more suspicion of a C5/C6 radiculopathy. While a unilateral diminished response of the brachioradialis and triceps reflex, but normal biceps reflex, may instead suggest a lesion of the radial nerve or posterior cord of the brachial plexus. And a final scenario: diminished or absent reflexes bilaterally throughout the body may indicate the presence of peripheral polyneuropathy (especially if the most distal reflexes like the ankle are diminished or absent bilaterally).

Reflex: Biceps

Procedure: With the patient’ relaxing their hands in their lap, place the tip of your thumb over the biceps tendon at the antecubital fossa. Tap your thumb with the reflex hammer.

Mediated By: C5/C6. Musculocutaneous nerve.

Reflex: Brachioradialis

Procedure: With the patient relaxing their hands in their lap strike the distal third of the radial/lateral and slightly anterior aspect of the forearm.

Mediated By: C5/C6. Radial nerve.

Reflex: Triceps

Procedure: Support the patient’s arm under the elbow with their arm relaxing downward in a 90/90 degree position. Strike the triceps tendon just proximal to the olecranon.

Mediated By: Primarily C7. Radial nerve.

Reflex: Quadriceps

Procedure: With the patient sitting with legs relaxed, strike the patellar tendon just distal to the patella.

Mediated By: L2/L3/L4. Femoral nerve

Reflex: Ankle

Procedure: Support the foot gently in a neutral ankle position and strike the achilles tendon.

Mediated By: S1. Tibial/Sciatic nerve

Upper Motor Neuron Reflexes

The presence of hyper-reflexive muscle stretch reflexes may have already clued you into the presence of an upper motor neuron lesion. Central nervous system pathologies are numerous, but to name a few: stroke, multiple sclerosis, traumatic brain or spinal cord injury, tumor, or cervical myelopathy. A few additional reflexes specific to upper motor neurons are described below.

Babinski Reflex

Procedure: With the tip of your reflex hammer handle, stroke the sole of the foot in an L shape from the heel towards the fifth toe then medially along the ball of the foot.

Interpretation: A normal response for a developed pyramidal system (after 1-2 years old) is toe flexion. This normal response is termed the flexor plantar reflex. An abnormal response is toe extension and splaying of the toes (again, because of a lack of descending inhibitory signals). This abnormal response is termed extensor plantar reflex or Babinski positive.

Hoffman’s Sign

Procedure: Grasp the patient’s hand and wrist in a relaxed position. Using your other hand, take the tip of their middle finger in a key grip and flick the tip of their middle finger downward with your thumb.

Interpretation: A normal response will have no response or reflex to the stimulus. An abnormal response is when the patient’s pointer finger and thumb reflexively twitch towards each other with the tip the middle finger is flicked.

Clonus Reflex

Procedure: Supporting the patient’s foot, perform a rapid dorsiflexion movement with some sustained resistance towards dorsiflexion.

Interpretation: A normal response will have no response or reflex to the stimulus. An abnormal response will manifest by the foot beating up and down. Count the number of beats the foot makes for documentation.

Cranial Nerve Screening

13 nerves originating from the brain or brainstem provide innervation to a wide range of functions with a combination of motor, sensory, and autonomic nerve fibers. Detailed below are methods to assess each cranial nerve.

CN I Olfactory

Function: Sensory from olfactory epithelium

Testing: Assess the ability to smell common scents.

CN II Optic

Function: Sensory from retina of eyes

Testing: Assess peripheral vision by having person read an eye chart.

CN III Oculomotor

Function: Motor to muscles controlling upward, downward, and medial eye movements, as well as pupil constriction

Testing: Assess pupil constriction as a reaction to light.

CN IV Trochlear

Function: Motor to muscles controlling downward and inward eye movements

Testing: Assess the ability to move the eye downward and inward by asking patient to follow your finger.

CN V Trigeminal

Function: Sensory from face and motor to muscles of mastication

Testing: Test sensation of face and cheeks as well as corneal reflex. Assess the patient’s ability to clinch the teeth.

CN VI Abducens

Function: Motor to muscles that move eye laterally

Testing: Assess patient’s ability to move eyes away from midline be asking them to follow your finger with their eyes.

CN VII Facial

Function: Motor to muscles of facial expression and sensory to anterior tongue

Testing: Assess symmetry and smoothness of facial expressions. Test taste on the anterior ⅔ of tongue.

CN VIII Vestibulocochlear

Function: Hearing and balance

Testing: Assess by rubbing fingers by each ear. Patient should hear both equally. Can also ask patient to perform balance test.

CN IX Glossopharyngeal

Function: Controls gag reflex and sensory to posterior tongue

Testing: Assess gag reflex and taste on the posterior tongue

CN X Vagus

Function: Controls muscles of pharynx, which facilitate swallowing. Provides sensory to thoracic and abdominal visceral region

Testing: Ask patient to say “ah” and watch for elevation of soft palate

CN XI Accessory

Function: Motor to trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles

Testing: Muscle testing of trapezius

CN XII Hypoglossal

Function: Motor to muscles of the tongue

Testing: Ask patient to stick tongue straight out. Tongue will deviate toward injured side

An abbreviated screening of cranial nerves can be performed as follows:

- Instruct the patient to follow a pen or the tip of your finger as you draw an “H” in the air. Observe each direction of eye movements for both eyes.

- Instruct the patient to look at the tip of your nose. Covering one eye at a time, pass a pen light across the open eye, observing pupillary constriction as a reaction to light.

- Instruct the patient to perform a few exaggerated facial expressions such as smile big, pucker the lips, open eyes wide, raise the eyebrows. Observe for asymmetries or gross abnormalities.

- Instruct the patient to stick their tongue out straight, then to open their mouth and say “ah”. Observe for tongue deviation and soft palate elevation.

What’s Next?

Having completed the neurologic exam, let’s return to the questions we intended to answer:

- Is there a lesion or dysfunction of the nervous system?

- Is the lesion or dysfunction likely coming from the central or peripheral nervous system (or both)?

- If it appears to be from the peripheral nervous system, can I narrow down the differential diagnosis list?

- Is another diagnostic test or outside referral necessary?

When the neurologic exam suggests a lesion or dysfunction of peripheral nerve(s), additional diagnostic information is needed to inform treatment and prognostic decisions. Even a thorough and careful neurologic exam cannot answer all the essential questions. For example:

- Is paresthesia and weakness in the feet due to an L5/S1 radiculopathy or a polyneuropathy?

- Is paresthesia of the fingers and weakened grip due to a median nerve compression, ulnar nerve compression, C8/T1 radiculopathy, or a combination of these? If it is a peripheral nerve compression such as carpal tunnel syndrome or cubital tunnel syndrome, how severe is it?

- If someone has pain and paresthesia in a distal “stocking and glove” distribution, do they really have a polyneuropathy? If so, is it due to demyelination or axon damage of nerve fibers? Are motor or sensory nerve fibers most affected? The answer to these questions can help determine what may have caused the polyneuropathy and available management options.

- Is foot drop due to an L5 radiculopathy or a fibular nerve compression?

The answer to these and other questions can be answered through nerve conduction and EMG testing (NCS/EMG).

Matthew Okelberry, PT, DPT, ECS, OCS

References

- Flynn, Cleland, Whitman. Users’ Guide To The Musculoskeletal Examination. Evidence in Motion, 2008.

- RapidScreeningforDiabeticNeuropathyUsingthe128HzVibration TuningFork(the“On-Off”Method). CanJDiabetes42(2018)S321.

- Fearon C, Doherty L, Lynch T. How Do I Examine Rigidity and Spasticity? Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2015 Mar 28;2(2):204. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.12147. PMID: 30363919; PMCID: PMC6183506.

- Kimura. Electrodiagnosis In Diseases Of Nerve And Muscle Principles and Practice. Fourth Edition. Oxford University Press, 2013.